How do we measure the weather?

How do we measure the weather and what do we use to measure it?

To be able to make the best weather forecasts we need to know, with as much detail and accuracy as possible, what the weather is doing right now. To do this we measure all the different parts of the weather and record it, this is called a weather observation.

Measuring temperature

Temperature is a measure of how much heat energy something has; when measuring the weather we usually want to know the temperature of the air.

To measure temperature we use a thermometer, you probably have one of these at home for taking your temperature when you are feeling poorly. We used to use thermometers that had mercury in them, but all of these are no longer used as mercury is dangerous if it were to leak out or the thermometer was to break. Instead we now use digital thermometers or alcohol thermometers.

To measure the temperature accurately we keep our thermometer a Stevenson screens. This is a white box with slats in it to allow air to flow through the box. Stevenson screens face north, which combined with their colour and slats, give us the best measure of the current temperature, without getting too hot in direct sunlight or being too cool in the shade.

Measuring humidity

Humidity is how much water vapour is stored in the air and is shown as a percentage; if the humidity is 100%, the air is saturated meaning it cannot hold any more water - this occurs when it is foggy and sometimes when it is raining, but usually it rains before the humidity gets this high.

We measure humidity, by first measuring the wet bulb temperature and then doing a calculation. The wet bulb temperature is measured similarly to the normal air temperature; we use a thermometer that has its end wrapped in some damp cloth and it is kept in a Stevenson screen with the thermometer.

Energy is needed to evaporate the water from the cloth and this causes the air around it to cool a little (from the loss of energy), which means the thermometer measures a lower temperature.

Using the temperatures from the two thermometers and equation we can calculate humidity.

Measuring wind

There are two properties of wind that we measure: direction and speed.

To measure the wind direction, traditionally, we used a weather vane, which would point to the direction the wind was coming from. When we talk about wind direction, we talk about where it has come from, not where it is going. This can tell us a lot about the weather, for example, when the wind is coming from the north, it is usually going to be a colder day, when it is coming from the south it is likely to be a warmer day.

To measure wind speed we use an anemometer, a piece of equipment that, traditionally, would spin when there is wind and how fast it spun would tell you how fast the wind is. These are often cups which spin through a beam of light to measure the wind speed and are placed 10m above the ground; this height helps avoid any problems with friction from buildings and other objects near the ground. The next time you are on a long car journey see if you can spot any of these on the side of the road.

New anemometers use sonar to measure the wind direction and speed at the same time; they do this by sending sonar between different sensors and depending on how long it takes for the signal to be received the sensors can tell what speed the wind is blowing at and the direction it is coming from. These anemometers are mostly on mountain sites as they can’t freeze like other anemometers can do in very cold conditions.

Measuring visibility

Visibility is how far we can see; often it is many kilometers, but when it is foggy it may only be a few metres.

To measure visibility we simply use our eyes! We look for 'vis points', these are objects that don't move that we know how far away they are so if we can see them we know that the visbility is at least that far or if we can't see it then we know it is less than that. You can do this yourself at home, if you look out of your window, what can you see? Your neighbour's houses? Some hills? Some tall buildings? Get your parents to help you find out how far away each of these things you can see is, then when you look out your window you will know if the shops 1km away are hard to see, but still just about visible, then you will know the visbility is 1km; if you can't see your neighbour's house, which is 50m away, you will know the visbility is less than 50m.

Although we do still use our eyes, we also use lasers where there aren't humans to check. These work by firing a beam of light in a straight line and measuring how long it takes to be bounced back, depending on how long this takes will give you the visibility.

Measuring cloud

To measure clouds, we need to know how much cloud there is in the sky, what height these clouds are at and what type of clouds these are. All of this can be done with our eyes, though we do have cloud-base recorders, which can do some of this for us by pointing lasers into the sky and seeing how long the beam of light takes to get bounced back and then works out how high the clouds are, they can also look at the sky and see how much is cloud and how much is clear skies.

When we measure the clouds with out eyes, to see how much cloud there is, the first thing we do is divide the sky into eight equal parts in our head, these parts are called oktas. If all eight boxes are completely full then the sky is overcast, if all eight boxes are empty then the sky is clear. When there is some cloud, but not completely clear or completely covered, then we have to estimate how much cloud there is by imagining how many boxes it would fill if it was all clumped together.

Measuring how high clouds are takes practice, but it helps when you have buildings and trees nearby that you know the heights of and see where the clouds are from their tops, it also helps to know what type of cloud you are looking at, because different types of cloud only occur at certain heights.

There is some technology that is working on being able to tell what type of cloud is in the sky, but this is still quite difficult for equipment to do, so we do rely on humans to do this. The video below teaches you how to spot clouds, what heights they are at and what kind of weather you will get with them.

Measuring rain

When measuring rain we look at two slightly different variables: rain rate and rain accumulation. Rain rate is the amount of rain falling out the sky and how quickly. Rain accumulation is how much rain has reached the ground over a certain amount of time. To measure rain accumulations we use rain gauges, these are buckets with sharp edges, traditionally 5 inches across, that capture rain and feed it into a bottle. These are then checked at set times to see how much rain has accumulated in that time.

We now mostly use tipping bucket rain gauges, these are very similar, but with a slight difference; inside there's no bottle, but little tipping buckets. This allows us to measure rain rates and rain accumulations at the same time. The little buckets are like a set of scales that can carry a specific amount of water, when one side of the scale gets filled with water it will tip and empty out its water and the other bucket will begin to fill. How quickly the buckets tip tells us how quickly the rain is falling and how many times the buckets tip in a set amount of time tells us how much rain fell during that time.

We also use radar to measure rain. Radar was developed during World War II to detect enemy transport, such as planes, ships and submarines, before it was realised that it can also be used to see where rain is falling. We now have 18 radar stations across the British Isles, including those in the Republic of Ireland and Channel Islands, scanning the skies for rain every 5 minutes. Radar works similarly to other pieces of equipment we've already looked at; the radar sends out waves and measure how long it takes for these to bounce back, which tells us where the rain is depending on how long it takes to come back. Radar can also tell us how heavy the rain is and we can use this to estimate the rain rates at the ground.

Measuring snow

Radar can be used to measure snow too, but because of the way radar works it can't tell us whether it is rain or snow that is causing the waves to bounce back. There are radars that can do this, as they can tell whether what they are bouncing off is liquid - rain, or frozen - snow by looking things like size and shape, and the UK has just finished upgrading its radar network to be able to do this.

We also need to know the snow depth at the ground, not just if it's falling out of the sky. To measure the snow depth all you need is a ruler! To get an accurate reading of the snow depth you need to choose a good point to take a reading, this would be somewhere flat that isn't sheltered by trees or buildings and is grassy. We measure over grass and not brick or concrete as these materials are warmer than grassy surfaces so will make the snow melt quicker.

We also use sensors to measure snow depth where there are no humans to go and check, these work by shooting a laser at the ground and seeing how long it takes to come back. The sensor knows how long it takes for the laser to bounce back from the ground, so if it returns quicker then it knows there is snow on top of it and how quickly it comes back will tell it the depth of the snow.

Measuring pressure

Pressure is important as it can tell us about what kind of weather to expect; when the pressure is high we can usually expect clear skies and light winds, when the pressure is low we can usually expect wet and windy weather. It is also very important for some businesses, for example aeroplanes need to know exactly what the pressure is so they know what height to fly at, as they don't measure height above the surface in metres or miles, they use pressure levels.

The pressure is measured using a barometer, you may have seen an old fashioned barometer at a museum or maybe someone in your family has one. These older barometers are very sensitive and need to be looked after to make sure they are still accurate, so most of the time now we use digital barometers as they are more reliable.

Measuring lightning

Lightning comes from thunderstorms, these are large storms with lots of rain, strong winds, sometimes hail and other hazardous types of weather as well as lightning. Lightning can be dangerous depending on where it strikes and can cause power cuts and other problems like fires, so it is very important to be able to tell where lightning is.

At the Met Office we use a network of sensors to detect lightning across the UK; when lightning occurs it sends out a signal that these sensors can pick up and depending which sensors pick it up, tells us where it is.

You can work out where lightning is coming from for yourself the next time there's a thunderstorm near you; thunder is the noise that lightning makes as it cracks through the sky, but because sound travels slower than light you always see the lightning first. So if you count the number of seconds between the lightning and the thunder and divide that number by 3 it will tell you how many kilometers away the lightning is. You can tell if the thunderstorm is getting closer or further away by seeing how the gap between the thunder and lightning changes between lightning strikes; if the gap is getting bigger between the lightning and the thunder then the storm is moving away, but if the gap is getting smaller then the storm is getting closer.

Location of weather stations

Weather stations are found throughout the UK, providing valuable data to our meteorologists.

Consistency of measurements is vital across the network, both for informing our forecasts and for the long-term weather and climate records of the UK.

To ensure consistency of measurements in the records, weather stations must meet strict criteria, in alignment with meteorological organisations across the world. This includes specific standards on the levels of grass-cover within the observations area, as well as having enough clear space for the weather station to be free from the influence of non-meteorological factors on the readings.

You’ll find weather stations located across the UK, often in wide open space so observations can be accurately recorded. For example, official weather stations are often located at airports as they have plenty of open space making them a good place for observations to take place. However, the observation equipment is set an internationally-agreed distance from the runway to ensure no external factors can influence readings in any way.

How do satellites measure the weather?

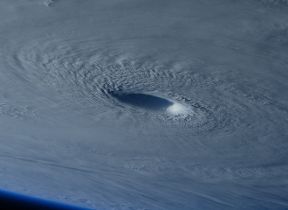

There are two main types of satellites - ones that orbit the earth and ones that stay fixed above a certain point above the Earths surface. We use these to measure lots of different aspects of the weather. You have probably seen pictures or videos from satellites looking at the Earth, these show us where the cloud is, what type of cloud it is, how high it is and how it is moving, but it also tells us things about the Earths surface, such as the temperature, information about plants and buildings, track volcanic ash, dust and sand in the atmosphere, changes in water and ice cover, but also what the winds are doing and how much water vapour is in the atmosphere.

What else measures the weather?

Most of the ways to measure the weather we have talked about, measure the weather over the land, but there are other parts of the Earth that we need to think about too.

Most of our planet, about 70% of it, is covered by our oceans, of which there are 5: Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic and Southern (also know as the Antartic) Oceans. So we need to be able to know what is going on in and over our oceans as this will affect what happens over the land.

To measure the weather over the oceans we use buoys; many of these measure the weather in the same way as we have talked about above, others measure different things about the oceans, like their temperature, how salty they are and where their currents flow.

We also need to measure upwards from the land and oceans to find out the weather through our atmosphere. We use weather balloons and aircraft to do this.

Some aeroplanes, including the ones you might fly on when you go on holiday, carry equipment to measure the weather along their route, usually pressure, wind, temperature and dew point. This can give us information from all over the world!

Weather balloons are released from set places over land, or from ships and climb the whole way through the troposphere (that is the layer of the atmosphere closest to the surface where our weather happens). They take measurements of pressure, wind, temperature and dew point as the climb; the balloon will get bigger and bigger as the pressure gets lower as it climbs and then bursts near the top of the troposphere.

Verifying records

All Met Office UK weather observations are subject to an internationally-agreed rigorous quality-control process. For new official records, we undertake further careful investigation to ensure that the measurement taken is robust, reliable, is feasible in the meteorological set-up and adheres to international World Meteorological Organisation standards. This is why you’ll often see observations records labelled ‘provisionally broken’ before the full verification has taken place, and for official confirmation of the record to be announced a few weeks later.

When a reading does not meet the required standards, it is rejected as an official record and expunged from the UK’s weather and climate observation records.

Observations from amateur stations and those not part of the Met Office’s official network cannot be considered for entry into the official records as they’re not subject to the same internationally agreed standards that are required for the official records.